Alugar um carro é fundamental para se locomover em Orkney. Eu tinha reservado um com a Drive Orkney em contato anterior por e-mail, e fui buscá-lo assim que botei o pé em terra firme, em Kirkwall. Por economia, havia escolhido um modelo com câmbio manual. Ao retirar o carro, o gerente me perguntou se eu tinha certeza disso, e respondi que não haveria qualquer problema, pois a vida toda dirigira apenas carros manuais. A cara dele me pareceu meio incrédula, mas a ficha só caiu depois de iniciar a jornada rumo a Stromness, onde ficaria hospedada por três noites: no UK, o volante fica do lado direito, portanto a alavanca de câmbio é acionada com a mão esquerda. Até adquirir um mínimo de destreza creio que fiz algumas barbeiragens. Felizmente não havia muito movimento na estrada.

Rent a car is mandatory to get around in Orkney Mainland.

I had booked one online with Drive Orkney, and picked it up as soon as I set foot in Kirkwall. For economy, I had chosen an old model with manual gear. The manager asked if I was sure about that, and I answered that it wouldn’t be a problem, because all my life I had driven manual cars. He made a skeptic face. Too late I realized that in the UK the steering wheel is on the right side, thus the driver uses the left hand to change gear: I was already on the road to Ring of Brodgar – before heading to Stromness, where I’d stay the next 3 nights. I made some horrible mistakes until I started to get used to it. Fortunately the road was quite empty.

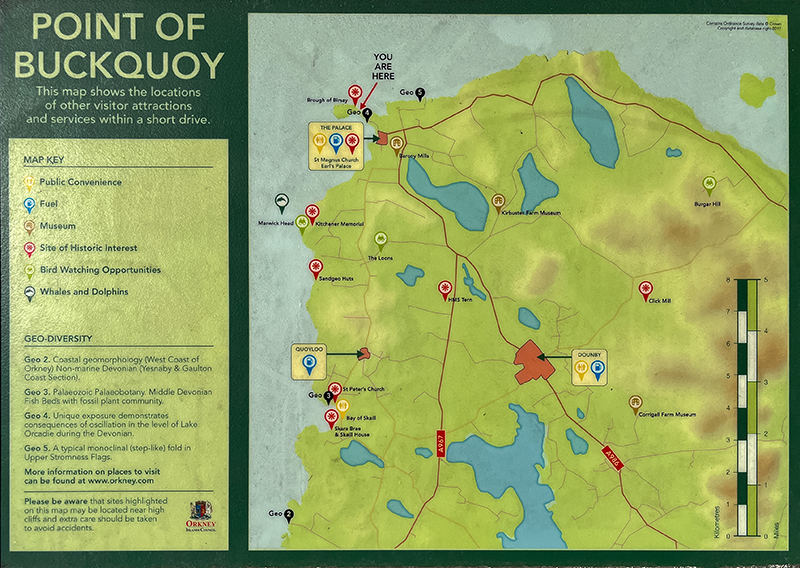

No dia seguinte, que amanheceu azul e ensolarado, fui visitar de novo o Ring of Brodgar, pois na véspera estava cheio de ônibus de turistas, e o dia muito nublado, o que atrapalhou as fotos. Acabei ficando a manhã toda lá, assim o sol já estava alto quando segui para visitar os Broughs (ou Brochs) de Birsay e de Gurness.

“Brough” e “Birsay” são palavras originadas do Norueguês antigo “Borg”, que significa “forte”, mas significam coisas diferentes. “Brough” se refere às defesas naturais da ilha; “Birsay” quer dizer ilha com um único acesso, por uma estreita faixa de terra. Assim sendo, Brough of Birsay é uma ilha cujo acesso só é possível durante a maré baixa, quando o caminho de concreto que a liga à terra firme fica exposto. Quando lá cheguei, a maré já estava subindo.

Next day was sunny, sky was blue, so I went back to the Ring of Brodgar. In the eve, it was crowded with tourism buses, the day was grey, my photos were therefore shitty. So I took my time under the sun, which was already high when I left, on my way to the Broughs of Birsay and Gurness. It’s not far.

The words ‘brough’ and ‘birsay’ both come from the Old Norse ‘borg’ (‘fort’), but their meanings are slightly different. ‘Brough’ refers to the natural defences of the island. ‘Birsay’ (previously byrgisey) means an island accessible only by a narrow neck of land. Brough of Birsay is a tidal island only accessible for around two hours in low tide, and it’s linked to headland by a concrete causeway visible only when the sea retreats. By the time I got there, tide was rising.

Before Kirkwall became the centre of power in the 12th century, Birsay was the seat of the rulers of Orkney. The extensive remains of an excavated Norse settlement and church overlay the earlier Pictish settlement.

O caminho de concreto tem 150 m de comprimento. Fica submerso na maré cheia, e as fortes correntes tornam a travessia perigosa. Antes de se aventurar é preciso checar os horários da maré, expostos no Centro de Informações de Turismo em Kirkwall, no Centro de Visitantes em Skara Brae ou no site da meteorologia (link abaixo) .

The concrete causeway is approximately 150m long.During high tide is submerged underwater and the strong tides here make it dangerous to cross. Low tide times are displayed in the Kirkwall Tourist Information Office and at the nearby Skara Brae Visitor Centre, or on the Met Office website:

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/forecast/

A ilha abriga vestígios de um importante assentamento Picto. Escavações comprovaram que este povo viveu aqui no fim do século VII. Os Nórdicos chegaram 200 anos depois, no século IX, e ainda são visíveis as ruínas de suas casa, celeiros, e mesmo uma sauna. Mais tarde, uma igrejinha e monastério foram construídos, mas usados por pouco tempo: não foram encontrados muitos artefatos medievais e a torre oeste da construção nunca foi completada.

The island hosts the remains of a substantial Pictish settlement. Excavations show that Picts lived here in the late 7th century. Norse people settled on the brough 200 years later, in the 9th century, and the remains of their houses, barns and even a sauna can still be seen. Later, a small church and monastery were built on Birsay. The church was only used for a short time; there were very few medieval artefacts discovered there, and the west tower of the building was never complet

Some of this settlement was washed away by coastal erosion in recent years, what has led to the construction of a concrete reinforcement cleverly sculpted to resemble the natural sandstone.

Os Vikings chegaram no século IX e seu assentamento se desenvolveu ali por três séculos. O processo de construção e reconstrução de estruturas criou um verdadeiro labirinto de paredes de pedra, umas por cima das outras. Ainda são visíveis algumas das “casas longas” Nórdicas, celeiros, oficina de ferreiro e mesmo uma sauna do século XI com piso aquecido! A ultima estrutura construída pelos Vikings foi a igreja, no século XII.

The Vikings arrived on the Brough of Birsay during the 9th century and their settlement there was developed over the next three centuries. The process of building and rebuilding structures has left a complicated maze of stone walls, one on top of the other. Remains of several Norse longhouses, barns and a smithy can still be seen today, as well as an 11th century sauna with underfloor heating! A 12th century church was the last of the structures built by the Vikings.

Os vestígios deixados pelos Pictos são um pequeno poço, as fundações por baixo das construções posteriores e uma importante coleção de artefatos, incluindo um conjunto de moldes sofisticados para fundição de metais, como bronze. Os Pictos eram exímios artesãos que tinham um estilo de vida refinado séculos antes da chegada dos Vikings. Fragmentos de vidro, alfinetes de osso e pentes foram encontrados misturados com os artefatos Nórdicos nas casas no Brough. Havia um cemitério Picto por baixo do cercado em volta da igreja Nórdica. Ali também foram encontrados os pedaços de uma pedra entalhada pelos Pictos, retratando três Pictos vestidos com túnicas longas, portando espadas e escudos quadrados, e outros símbolos. Em Birsay mesmo puseram uma réplica; a original está no Museu Nacional da Escócia, em Edimburgo.

The Pictish settlement is attested by a small well, foundations under the later buildings and an important collection of artifacts, including a group of moulds for fine metalworking. Pictish people were skilled craftsmen who led a sophisticated lifestyle for several centuries before the Vikings arrived. Fragments of glass, bone pins and combs were found amongst Norse artefacts in houses on the Brough.

The enclosure round the Norse church overlies a Pictish graveyard .

An important Pictish carved stone was found in pieces in this enclosure. It shows a striking procession of three Picts dressed in long robes and bearing spears, swords and square shields. The stone in Birsay is a cast; the original is in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.