O monumento mais antigo deste Patrimônio Mundial.

Escavações mostraram que este sítio era, originalmente, um círculo de pedras – possivelmente o mais antigo nas Ilhas Britânicas. Embora atualmente não exista mais o fosso ao redor das pedras – desgastado por séculos de lavoura – confirmaram que o mesmo tinha dois metros de profundidade, cercando uma área de 44m de diâmetro. Originalmente havia pelo menos 11 monolitos, dos quais restam apenas 4, e alguns cotocos.

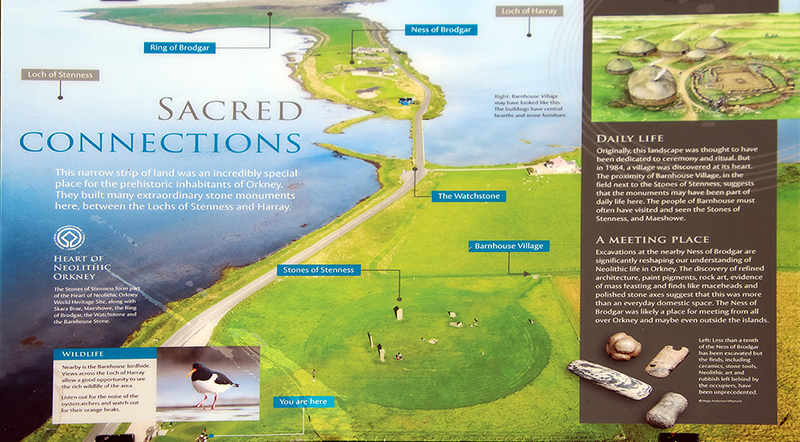

Although the site today lacks the encircling ditch and bank, excavation has shown this site was a henge monument, possibly the oldest in the British Isles. In Neolithical times, the stone ring had been entirely surrounded by a ditch, two metres (6.5 ft) deep, surrounding an area 44 metres (144 ft) in diameter. Centuries of ploughing have almost entirely removed the henge which once enclosed the (at least 11) standing stones, of which only four survive today, and some stumps.

Em dezembro de 1814, um fazendeiro resolveu remover as pedras, pois lhe incomodava a quantidade de gente que invadia a propriedade para fazer rituais junto às pedras. Ele começou demolindo a Pedra de Odin, para ultraje geral. Quando, por fim, conseguiram fazê-lo parar, ele já tinha derrubado duas outras pedras.

A Pedra de Odin, à qual se atribuíam poderes mágicos, ficava ao norte do círculo. A pedra tinha um furo circular, através do qual casais tradicionalmente davam as mãos para assumir seu compromisso. Outras cerimônias eram realizadas ali, inclusive promessas e juramentos eram feitos pondo a mão na pedra – o chamado Voto de Odin.

In December 1814 a tenant farmer in the vicinity of the stones, decided to remove them on the grounds that local people were trespassing and disturbing his land by using the stones in rituals. He started by smashing the Odin Stone. This caused outrage and he was eventually stopped, but two more stones had already been destroyed.

The Odin Stone, believed to have magical power, stood in the field to the north of the henge. It was pierced with a circular hole, and was used by local couples for plighting engagements by holding hands through the gap. Other ceremonies took place there, including the “Vow of Odin” – a tradition of making oaths or promises with one’s hand in the Odin Stone.

Análise geológica dos monolitos revelou que cinco diferentes tipos de pedras foram utilizadas. Esta descoberta reforça a teoria de que, assim como em Brodgar, as pedras foram trazidas de diferentes lugares, provavelmente significativos, para a construção do monumento.

A construção de um círculo de pedras envolvia considerável esforço da comunidade, envolvendo atividades “especializadas” como planejamento, extração das pedras, transporte, construção de fundações e a construção final. Os círculos mais antigos no Reino Unido – Stenness e Callanish (este na Ilha de Lewis) – foram construídos alinhados com a posição do Sol e da Lua. Mas não há consenso entre os arqueólogos quanto à sua função. Poderiam ter sido locais cerimoniais, rituais, sociais, mortuários, para reuniões comunitárias…ninguém sabe ao certo. Eu acrescentaria pontos de comércio a essa lista de possibilidades.

Geological examinations of the surviving stones revealed that five different types of stone were used – a discovery that reinforces the theory that the stones for the monument, just like Brodgar, were brought to the site from various different, perhaps significant, locations.

A stone circle construction often involved considerable communal effort, including specialist tasks such as planning, quarrying, transportation, laying the foundation trenches, and final construction. The two oldest stone circles in Britain – Stenness and Callanish (this on the Isle of Lewis) – were constructed to align with solar and lunar positions. But no consensus exists among archaeologists regarding their intended function: places of ceremony, worship, burial grounds, social gathering places… nobody knows for sure. I’d add trade spots to the list.