O motorista, que também é dono de um dos dois mercados da cidade, já tinha compromissos naquele dia e não podia fazer um tour completo para mim, mas sugeriu me levar aos lugares, me deixando por uma ou duas horas enquanto fazia outras coisas. Desta forma pude visitar o Castelo de Noltland, o farol em Noup Head e Castle O’Burrian- o habitat dos puffins – antes da forte chuva que caiu à tarde. Dei graças aos céus por não ter conseguido alugar uma bicicleta.

Depois de visitar o Castelo, avistei a van vindo me buscar no horário combinado. O motorista, ao abrir a porta, perguntou se eu tinha perdido alguma coisa… e já me entregou uma lente, que havia caído da minha mochila sem eu perceber! Me dei conta que o zíper ficara aberto, e quase imediatamente avistei na grama do chão o par de meias extra que também tinha guardado no mesmo bolso da mochila.

The driver, who also owns one of the two local stores, could not take me to a full day tour because he already had commitments, but suggested to take me to some places of interest, leave me there and pick me up after a while, in-between his appointments. So I could visit the Noltland Castle, Noup Head Lighthouse and Castle O’Burrian, the puffins habitat, before the hard rain that fell in the afternoon. I praised the Gods for having NOT found a rental bicycle.

After visiting the Castle, when the van came to pick me up, the driver asked if I had lost anything… and handed me one of my lens, that had fallen from my backpack without me noticing it! I realized that the zipper was open, and almost immediately saw, lying on the grass of the parking lot, the extra pair of socks that I had put in the same pocket.

O que não percebi foi que tinha posto, por pressa ou por engano, meu cartão de crédito no mesmo bolso. Como tinha pago quase todas as despesas online, não precisei do cartão até o dia seguinte, quando desembarquei do ferry em Kirkwall, e percebi que não estava em parte alguma. Tirei tudo da mala e da mochila, e nada. Já ia contactar o banco para fazer o cancelamento, quando recebi uma mensagem do motorista em Westray. Um casal de turistas tinha encontrado o cartão no estacionamento do castelo, e deixado com a atendente no mercado dele! Nem acreditei. E o melhor, eu nem precisaria voltar a Westray para buscar, pois no dia seguinte um funcionário ia com o caminhão para buscar produtos em Kirkwall. Ficou combinado que eu o encontraria na chegada do primeiro ferry. Mandei uma foto e minha descrição para a pessoa me reconhecer e fui tomar uma pint para comemorar. Aliás tomei uma taça de champagne.

Se tivesse que voltar a Westray, perderia mais da metade do dia seguinte no ferry, entre ida e volta. Ia arruinar meu cronograma, pois tinha reserva de duas noites em Rousay, outra das ilhas Orkney, conhecida como o “Egito escocês” devido à quantidade de sítios arqueológicos. O ferry para Rousay saía de outro porto, Tingwall, e embora os horários dos ônibus fossem coordenados com a chegada e saída dos barcos, eu só chegaria lá no fim da tarde. Felizmente, às 10 da manhã do dia seguinte, quando o ferry atracou vindo de Westray, logo vi o caminhão do mercado encostando numa vaga e um escocês bonitão vindo ao meu encontro. Nos identificamos, e ele, sorrindo, me entregou um envelope, no qual alguém escrevera meu nome e descrição: cabelos castanhos, óculos, com uma mala, uma mochila e uma câmera pendurada. Na verdade acho que estava rindo da minha cara. Quem poderia ser tão pateta para perder o cartão de crédito no meio de uma viagem?!? De toda forma, agradeci a ele e a todos os demais envolvidos e me despedi com dois beijinhos. Dentro do envelope estava meu cartão, intacto.

What I didn’t remember was that, for some reason, I had put my Credicard in that same pocket instead of keeping it in my wallet as usual. As most expenses had been paid online, I didn’t think about it until the next day, after getting off the ferry in Kirkwall. I searched thoroughly all my luggage. The card was nowhere to be seen. I was going to contact the bank to cancel it when a message came through. It was my guide Jonathan. A couple of tourists had found my card in the parking lot and returned it to the clerk in the driver’s store. I couldn’t believe my ears. People knew I had made the Papay tour with Jonathan, therefore he had my contact.

The best was that I would not need to go back to Westray to retrieve my card. The next day, 7th June, was a Wednesday, the store truck was going to Kirkwall for supplies. I should just meet the driver at the ferry station, which was right across the street. So I sent him my picture and description, and went for a celebration pint. Actually, I ordered a glass of Champagne.

If I had to go back to Westray I’d practically lose the next day, taking the ferry there and back. That would ruin my plans. I had a booking for next two nights in Rousay, another of the Orkney Islands, called “the Scottish Egypt” for its archaeological sites. The ferry to Rousay left from another harbour, Tingwall, and although the bus timetables were coordinated with the vessels, I’d only get there late in the afternoon.

Fortunately, next day at 10 a.m. I saw the ferry docking and, among the disembarking vehicles, the store truck. It parked and out of it came a handsome Scotsman walking towards me. He had my description ( brunette, prescription glasses, with a suitcase, a backpack and a camera) written in an envelope, which he gave me with a smile. I believe he was actually laughing at me. Who could be so stupid as to lose the credit card in a trip? Anyway, I was so thankful! Returning the smile, I expressed my everlasting gratitude and kissed him goodbye. Inside the envelope was my credit card, safe and sound.

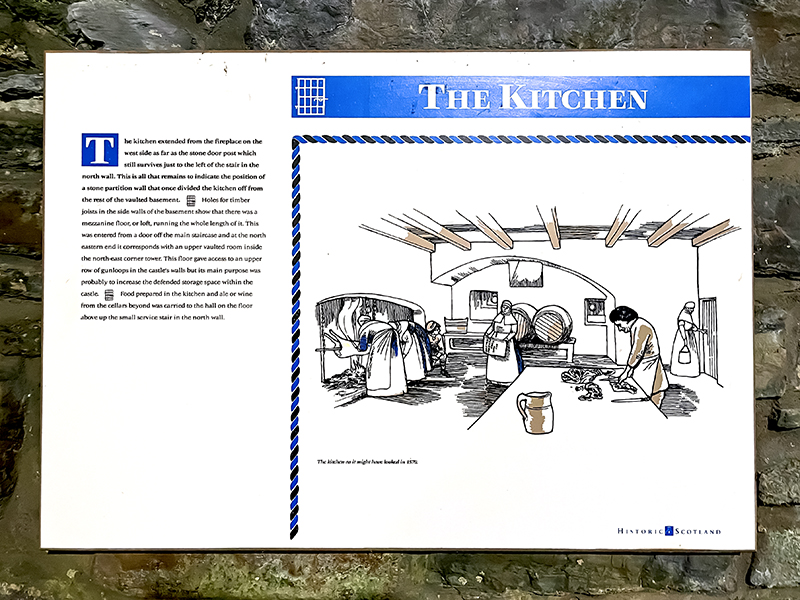

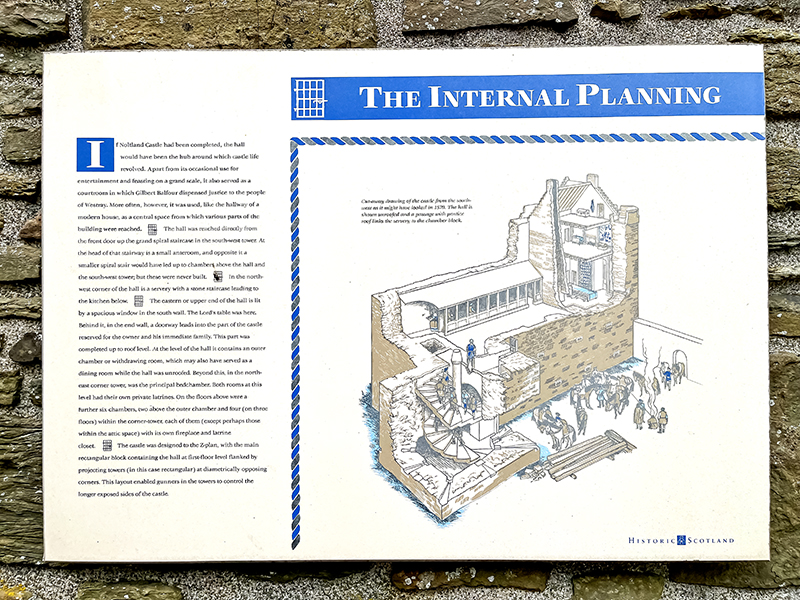

The castle dates mainly to the later 16th century, although it was never fully completed. what is on view today was the work of different hands at different times.

The Castle is notable for its defensive architecture, unusual for the period, with 7 ft thick walls.

Built on a slope overlooking Pierowall Bay, anyone approaching the castle, from any direction, would be spotted easily. 71 gunloops provided the opportunity to shoot at enemies from any angle. The lower floors, hav no accessible windows that could be exploited in an assault.

Gilbert Balfour, who built the castle, was not a good person. Master of the Royal Household to Mary, Queen of Scots, and was involved in the plot to kill her second husband. Balfour ended up executed for treason in Sweden in 1576.