Skara Brae was inhabited before the Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge were built

A aldeia Neolítica de Skara Brae foi descoberta no inverno de 1850 quando uma tempestade carregou a grama e areia de dunas junto à Baía de Skaill, expondo as ruínas de construções de pedra. Skara Brae é considerada, até os dias de hoje, a mais bem preservada aldeia Neolítica no Norte da Europa – não apenas pela antiguidade, mas especialmente pelo grau de preservação. As estruturas das casas e o mobiliário, enterrados na areia, se mantiveram em condições impressionantes. Em nenhum outro lugar no norte da Europa foi encontrado testemunho tão rico da vida desses povos ancestrais.

The Neolithic village of Skara Brae was discovered in the winter of 1850. Wild storms ripped the grass from a high dune beside the Bay of Skaill, and exposed an immense midden (refuse heap) and the ruins of ancient stone buildings. The discovery proved to be the best-preserved Neolithic village in northern Europe. And so it remains today. Skara Brae is remarkable because of its age, and even more so for the quality of its preservation. Its structures, buried in sand, survived in impressive condition – as did, incredibly, the furniture in the village houses. Nowhere else in Western Europe can we see such rich evidence of how our remote ancestors actually lived.

Arqueólogos acreditam que a aldeia ficava bem mais longe do mar, junto a um pequeno lago. Depois de séculos de erosão, agora se encontra bem na orla da Baía de Skaill, e não se sabe o tamanho original da aldeia, nem a extensão destruída pelo mar. Apesar do muro de proteção que foi construído, o sítio ainda é bastante vulnerável à elevação do nível do mar, fortes chuvas e tempestades.

Archaeologists believe it was originally built next to a small loch, farther from the sea than it is today. After centuries of erosion, Skara Brae now stands right by the shore of the Bay o’ Skaill and we don’t know how large the settlement was nor how much of it has been lost to the sea. The site is now protected by a seawall, but it’s still extremely vulnerable to rising sea levels, increased rainfall and severe storms.

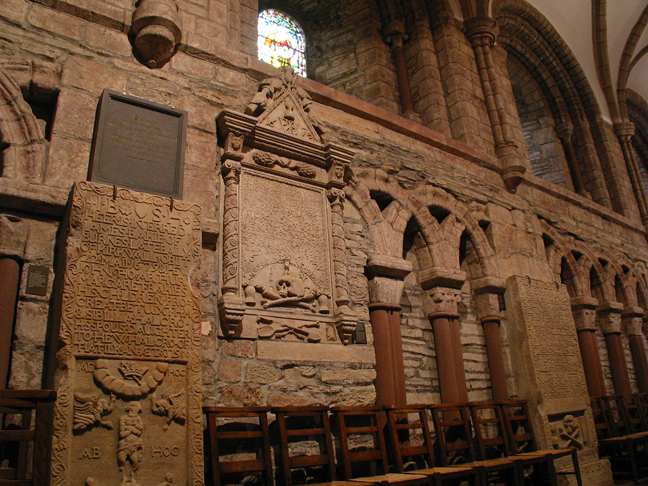

A aldeia é formada por habitações de apenas um cômodo, medindo aproximadamente 40 m2, retangulares com os cantos arredondados, e apenas uma entrada estreita, que podia ser fechada com um bloco de pedra – a mesma “flagstone” da qual todas as casas eram construídas. As unidades eram interligadas por passagens que vieram a ser cobertas ao longo do tempo, trazendo mais estabilidade e isolamento térmico, tipo um abrigo subterrâneo, super necessário no rigoroso inverno de Orkney.

The village consisted of several one-room dwellings, each 40 square metres (430 sq ft) average rectangle with rounded corners, entered through a low, narrow doorway that could be closed by a stone slab. All houses are well-built of closely-fitting stone slabs. They were set into large mounds of midden (household refuse) and linked by passages. Research shows that the passages were covered at some point, providing the houses with more stability and insulation against Orkney’s harsh winter climate (earth-sheltering).

A mobília toda em alvenaria consiste numa “estante” em frente a uma lareira central para cozinhar alimentos e aquecimento; duas camas caixote, assentos, caixas de armazenagem e pequenos “tanques” pelo chão, onde talvez armazenassem iscas para pesca. Algumas casas apresentam um sistema de esgoto primitivo com “vasos sanitários” : uma pequena ante-câmara, parcialmente coberta, com água e drenagem. Os encanamentos de todas as casas se conectavam num sistema de esgoto que escoava a sujeira para fora da aldeia.

The ‘fitted’ stone furniture within each room comprised a “cupboard” in front of a hearth centrally placed for heating and cooking, two box beds, seats, storage boxes and small tanks set into the floor, perhaps for preparing fish bait. A number of dwellings offered a small connected antechamber, with access to a partially covered stone drain, with water used to flush the waste away. The drains from the individual huts emptied into a sewer system which connected the entire village.

Ossos encontrados no local mostram que os habitantes comiam principalmente carne de gado e ovelha. Caçavam também cervos e javalis. As peles de todos esses animais eram aproveitadas. Consumiam peixes, crustáceos e carne de foca, assim como ovos de aves marinhas, e também as próprias aves. Cultivavam cevada e trigo nos campos próximos. Para fazer fogo usavam estrume e algas marinhas secas e, talvez, madeira trazida pela correnteza, embora madeira fosse algo muito valioso para ser usado como combustível – praticamente não há árvores em Orkney.

Bones found in the place show that cattle and sheep formed the main part of the Skara Brae diet. Deer and boar were also hunted for their meat and skins. Fish, shellfish and seal meat were consumed and people probably collected the eggs of seabirds as well as the birds themselves. Barley and wheat were grown in the surrounding fields. Animal dung and dried seaweed were burned in their hearths and perhaps driftwood too, although that was a valuable asset to be used as fuel, because trees are practically non-exhistant in Orkney.

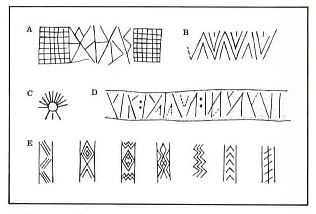

Escavações trouxeram à luz uma enorme variedade de artefatos, feitos de ossos (de animais, peixes, aves e mesmo baleia), marfim de baleia e de morsa, dentes de orca. Eram dados, miçangas, ferramentas (facas, agulhas, pás, enxadas); cerâmica e jóias – colares, pendentes e alfinetes de marfim de até 25cm. Destacam-se objetos de pedra ricamente entalhados. Os habitantes de Skara Brae eram fazendeiros, caçadores e pescadores capazes de, com ferramentas toscas e tecnologia rudimentar, fazer objetos belos e sofisticados.

A rich array of artefacts – made of animal, fish, bird, and whalebone, whale and walrus ivory, and orca teeth – has been discovered during the various archaeological excavations: gaming dice, hand tools like awls, needles, knives, beads, adzes, shovels; pottery and jewellery including necklaces, beads, pendants and ivory pins up to 9.8 in long. Most remarkable are the richly carved stone objects.These villagers were farmers, hunters and fishermen, capable of producing items of beauty and sophistication with rudimentary technology.

Skara Brae foi habitado durante 600 anos, coincidindo com a época em que os demais monumentos que formam o Coração Neolítico de Orkney foram construídos e estiveram em uso. As casas na aldeia foram construídas, reformadas e reconstruídas até 2500 AC, quando o clima ficou muito mais frio e úmido, possível razão para o abandono do local.

The site was continuously occupied for around 600 years (from 3180 BC to about 2500 BC), around the time the other four sites making up “The Heart of Neolithic Orkney” were built and in use. Houses were built, altered, replaced by new structures until around 2500 BC, when the climate changed, becoming much colder and wetter, so the settlement have possibly been abandoned by its inhabitants for this reason.

Cafe at Visitor’s Centre. Skara Brae greets more than 100.000 visitors/ year.